28/03/13

Julia Pfeiffer:

Figures of the Thinkable

Maria Stenfors

27 February – 6 April

2013

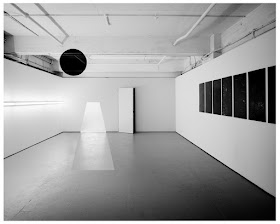

Walking in to Maria Stenfors’ lofty gallery, you are

currently faced with an amazing sight: a wall of clay, cracked and dessicated,

barren and bare (Building the

Labyrinth, 2013). It could be one of Alberto Burri’s Cretti, but it’s not. It’s a shrine to

all that has been, has failed to be, could still be, but isn’t yet. Representing

the full life cycle of her works, Berlin-based artist Julia Pfeiffer has

constructed this wall of clay, slathered on to the existing gallery wall with

thick palette knife strokes, out of discarded off cuts from failed and unwanted

works, which she allowed to dry right out, before adding water and remoulding

them almost as paint. Underneath are layers of actual paint, which could themselves

be depicting an image – but who can know, or ever will? The wall is heavy, not

only with the weight of the material, but with the possible figures and forms

that abide therein.

And as you stand and ponder the imponderable, you are,

yourself, being watched. For behind you, lined up in an intimidating row, are

eight eyes, staring penetratingly ahead (Iris

Studies, 2013). Made of ceramic, and glazed with special pens which

allow colour to be applied in a painterly manner, these extracted eyeballs gaze

voyeuristically, dreaming the dream of what might have been and what may still

develop. Removed from their surrounds, they are no longer figurative, but

purely symbolic. Freud, no doubt, would have had a scopophilic field day.

Pfeiffer doesn’t just work with clay, but also with canvas,

which she paints with grand expressionistic gestures, spread out on the floor,

before hanging the resulting scene as a backdrop for an installation, which,

itself, then becomes a black and white photograph. There are four of these on

display, each depicting an equally uncanny interior, none of which actually

exists. That said, the toppling

liquid-filled dog, which occurs first in Stages

(Vessel Tilting) (2013), does also feature in the exhibition, as a vision

made real: the possible made actual, a dream become reality (Animal Vessel (Figure of the Unthinkable),

2013). But distorted as ever, the ceramic creature must sit upon two supports,

as his oversized genitals hang down uncomfortably in between.

Whilst, in this instance, an image has become an object, a

ceramic slab standing upon an easel nearby renders a 3D character from a mug (sadly

not on display) almost as flat as a painting (Body Relief (Figure of the Thinkable), 2013). Here, the woman, whose breasts

on the mug are, so I am told, doomed to tip up every time the drinker takes a

sip, has been relieved of her physical discomfort and elevated in status from a

mildly distasteful comic item to a virtually 2D work of art – the reverse fate

of the pitifully encumbered dog.

This sense of humour permeates much of Pfeiffer’s work, and,

again, one can but imagine the father of psychoanalysis’s joy at many of the

innuendos and interpretations offered up. Indeed, to return to the wall of

broken dreams, with its visions of the past, present and future, and the eyes

which gaze eternally upon it, trying to make something out of the blank canvas

it offers – what more is this exhibition than an invitation to the visitor to

unleash his or her own imagination as to how the story might unfold?

Images:

Building the Labyrinth

2013

Iris Study: blue

2013

Stages (Vessel Tilting)

2013

Animal Vessel (Figure of the Unthinkable)

2013